[]

= 1140 ) { /* large monitors */ var adEl = document.createElement(“ins”); placeAdEl.replaceWith(adEl); adEl.setAttribute(“class”, “adsbygoogle”); adEl.setAttribute(“style”, “display:inline-block;width:728px;height:90px”); adEl.setAttribute(“data-ad-client”, “ca-pub-1854913374426376”); adEl.setAttribute(“data-ad-slot”, “8830185980”); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); } });window.addEventListener(“load”, function(){ var placeAdEl = document.getElementById(“td-ad-placeholder”); if ( null !== placeAdEl && td_screen_width >= 1019 && td_screen_width = 768 && td_screen_width < 1019 ) { /* portrait tablets */ var adEl = document.createElement("ins"); placeAdEl.replaceWith(adEl); adEl.setAttribute("class", "adsbygoogle"); adEl.setAttribute("style", "display:inline-block;width:468px;height:60px"); adEl.setAttribute("data-ad-client", "ca-pub-1854913374426376"); adEl.setAttribute("data-ad-slot", "8830185980"); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); } });window.addEventListener("load", function(){ var placeAdEl = document.getElementById("td-ad-placeholder"); if ( null !== placeAdEl && td_screen_width

“In every tradition, if you listen closely, you’ll hear a story waiting to be remembered.” I saw this come alive for Rajasthani Art.

Table of Contents

= 1140 ) { /* large monitors */ var adEl = document.createElement(“ins”); placeAdEl.replaceWith(adEl); adEl.setAttribute(“class”, “adsbygoogle”); adEl.setAttribute(“style”, “display:inline-block;width:360px;height:300px”); adEl.setAttribute(“data-ad-client”, “ca-pub-1854913374426376”); adEl.setAttribute(“data-ad-slot”, “7048430498”); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); } });window.addEventListener(“load”, function(){ var placeAdEl = document.getElementById(“td-ad-placeholder”); if ( null !== placeAdEl && td_screen_width >= 1019 && td_screen_width = 768 && td_screen_width < 1019 ) { /* portrait tablets */ var adEl = document.createElement("ins"); placeAdEl.replaceWith(adEl); adEl.setAttribute("class", "adsbygoogle"); adEl.setAttribute("style", "display:inline-block;width:336px;height:280px"); adEl.setAttribute("data-ad-client", "ca-pub-1854913374426376"); adEl.setAttribute("data-ad-slot", "7048430498"); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); } });window.addEventListener("load", function(){ var placeAdEl = document.getElementById("td-ad-placeholder"); if ( null !== placeAdEl && td_screen_width

Toggle

Over the past few years, I’ve traveled across India, immersing myself in traditional art forms – learning not just how they’re made, but why they matter. While each region held its own creative treasure, Rajasthan in particular felt like walking through a living museum of color, rhythm, devotion, and story. From temple walls to textile prints, the Rajasthani art I experienced wasn’t separate from life – it was life. More than just observing it, I practiced these forms with local artisans, and in doing so, deepened my understanding of their sacred roots, their craftsmanship, and their soul.

Miniature Painting – Jodhpur’s Jewel of Precision

I learned the fine Rajasthani art of miniature painting in Jodhpur, at the Umaid Art Gallery, run by a fascinating artist known as the “Lentil Man.” Famous for painting on grains of rice and lentils so tiny you need a magnifying glass to see his work, his mastery over precision left me speechless.

Miniature painting, though tiny in scale, holds massive cultural depth. It flourished under royal patronage in the 16th century, combining multiple Indian themes. Rajput kingdoms like Mewar, Marwar, and Kishangarh had their own local flavor, depicting scenes from epics, court life, and love stories.

What makes this art so compelling is its use of natural pigments – lapis lazuli for blue, cinnabar for red, malachite for green, and 24 carat gold and silver leaf for accents. These are hand-ground, mixed with gum Arabic, and applied with brushes made from squirrel hair.

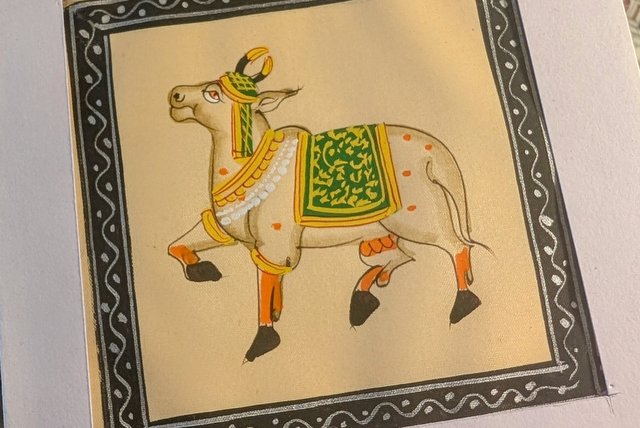

Under the Lentil Man’s guidance, I painted a decorative cow – a sacred and recurring motif symbolizing abundance, protection, and divinity. Each bell, garland, and curve was rendered with painstaking detail. What seemed like a technique quickly revealed itself to be a philosophy: slow down, be present, and pour attention into the tiniest of details. Miniature painting taught me that devotion isn’t always loud; sometimes it’s whispered in lines smaller than a grain of rice.

Pichhwai Painting – Udaipur’s Devotional Canvas

My journey with Pichhwai began in Udaipur, where I trained at the Indigo Art School, founded by Manoj, an artist with a dream far bigger than just his own brush. Manoj also runs a Guest House, a whimsical home-stay where every wall, ceiling, and corner is painted – no inch is left untouched.

Pichhwai painting is a 400-year-old devotional Rajasthani art form from Nathdwara, created primarily to adorn the sanctum of the Srinathji temple. These large textile scrolls depict Puranik events, festivals, and the divine lilas or sports of Sri Krishna, specifically in his Srinathji avatar.

The name “Pichhwai” literally means “that which hangs at the back.” Traditionally, these works served as backdrops behind the Murti and changed with the seasons – Sharad Purnima, Janmashtami, Annakut, Holi – all beautifully represented.

The pigments are made from natural materials: soot for black, turmeric for yellow, indigo for blue, and real silver and gold for divine accents. Painting a Pichhwai felt like joining a centuries-old prayer. Every cow was not just a cow – it was Kamadhenu, the wish-fulfilling being. Every lotus was not just a flower – it was a cosmic seat.

These works are not merely decorative – they are offerings, spiritual maps and singing clothes.

Bhitti Chitra & Nail Art – Living Walls & Tiny Canvases at Shilpagram

Udaipur offered yet another treasure: Shilpagram, an artisan’s village nestled among hills, alive with craft, music, and rustic beauty. It was here that I met Satyanarayan Dhabhai, an expert nail artist whose precision and dedication were absolutely astonishing. Using ultra-fine brushes, he painted delicate designs—florals, animals, mythological motifs – onto individual fingernails with stunning intricacy. Some of his miniature work could only be fully appreciated through a magnifying glass. Watching him work felt like witnessing art meet meditation. Every nail became a canvas; every detail, no matter how tiny, carried intentionality. He spoke about nail art as a form of everyday elegance, where tradition meets fashion, and how he often infused his designs with folklore or spiritual symbols passed down through generations.

My time in Udaipur also included working on Rajasthani Art of bhitti chitra-mural art on haveli walls, where I painted scenes of village life, animals, and gods with traditional brushes made from cloth-tied bamboo sticks. The lime-plastered surfaces, pigments of ochre, chalk white, and indigo, and the blessings embedded in every image gave the work purpose beyond decoration. These murals are not just art; they are protection, celebration, and identity etched into architecture.

What touched me most was how community driven this art was. Villagers would come to watch and even offer input, describing deities they revered or motifs from their childhood homes. Each wall tells a story of belonging. I saw grandmothers recount rituals while toddlers dipped their fingers in paint. In Shilpagram, art was both a memory and a mirror, revealing who the community was and who they hoped to become. It wasn’t about perfection; it was about preservation. In that shared act of painting, I felt stitched into the very fabric of Rajasthan’s living heritage.

Blue Pottery – Alchemy in Jaipur

In Jaipur, I explored a completely different medium – ceramics – at Sri Kripa Blue Art Pottery. Jaipur blue pottery, unlike most ceramics, uses no clay. Instead, it’s made from a unique quartz-based dough mixed with glass, multani mitti or Fuller’s earth, borax, and gum, then fired at a low temperature.

This makes the pottery more fragile but gives it a rich, glassy translucence. The technique was nurtured under the patronage of Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II in the 19th century.

The hallmark of blue pottery is its color palette – cobalt blues, turquoise, and greens – painted in floral and geometric designs that feel like delicate whispers from the royal gardens. I painted bowls and tiles with arabesques, lotuses, and carnations. There was something grounding about the process – kneading, shaping, painting, glazing, and waiting.

Like a quiet spell in the kiln, it reminded me that beauty takes time, and fragility has its own strength.

Indo-European Murals – Fusion in Fresco at Jodhpur Palace

In a lesser-known Jodhpur palace, I encountered something entirely unexpected – murals of the Ramayana and Mahabharata with flowing togas, Greco-Roman postures, and Mediterranean-style frescoes. These were the works of Polish artist Stefan Norblin, whose Indo-European style emerged from the fusion of cultures during colonial times. Greek columns stood behind Hanuman leaping across skies, and Indian gods wore European expressions. These hybrid murals whispered of cross-cultural memory, of stories that travel, blend, and evolve.

What fascinated me was the way Norblin’s art bridged East and West – not by diluting either tradition but by honoring both. His use of light and shadow, the theatrical drapery, and the anatomical precision borrowed from Renaissance influences sat comfortably alongside Indian sacred themes. I spent hours sketching and later re-imagining these pieces in pen and ink, merging Eastern symbols with Western forms.

One detail that especially caught my eye was the armor and headgear worn by Arjuna and Krishna in the murals. Instead of the usual dhotis and mukuts seen in Indian iconography, they were depicted wearing breastplates, pleated tunics, and crested helmets – remarkably similar to those worn by ancient Greek gods and warriors. Their stances echoed classical sculptures, with contoured muscles and poised, almost Hellenistic expressions. It was as if they had walked straight out of a mythological fresco in Athens and into the pages of the Mahabharata. This stylistic blend didn’t lessen their divinity – instead, it expanded it, showing how stories transcend culture, picking up new forms and aesthetics as they move. Through Norblin’s vision, Krishna became not just a Hindu deity but a global archetype of wisdom and strategy, while Arjuna stood as the timeless seeker, his bow as symbolic as any philosopher’s scroll.

It reminded me that age old stories aren’t fixed – they move, breathe, and absorb everything they touch. These murals weren’t just paintings; they were conversations across time and geography. They challenged the idea of purity in tradition and made space for collaboration, adaptation, and layered identity. In them, I saw a reminder that cultural boundaries are meant to be crossed—gently, curiously, and with reverence.

The Spirit of Sacred Craft

Each of these experiences wasn’t just about learning a Rajasthani Art or craft – it was about entering a lineage, honoring a rhythm, and letting art reshape how I saw the world. Rajasthan gave me not only skills but a deeper reverence for tradition and a stronger instinct for storytelling through form, color, and silence.

What struck me most was how none of these traditions felt like “past tense.” They were alive—in the hands of the artisans, in temple rituals, in festivals, and even in the streets. They were not museum pieces but acts of devotion and identity. Whether it was grinding pigments, stringing tiny bells in a border, or painting a lotus petal for the fiftieth time, every gesture was sacred.

In a world that moves fast, traditional art reminds us of the power of slowing down, of listening, and of creating something with presence.

I walked away from Rajasthan not just with paintings, but with imprints of conversations, philosophies, and ways of seeing that will stay with me forever. As a traveler, artist, and storyteller, I now carry these traditions in my own voice, hoping to share their spirit with every brushstroke and every word.

About the Author

Divya Ramachandran is a passionate artist, Founder of The Happy Wall Project, children’s book author, and storyteller with a flair for drama and theatre. With a background in teaching and a love for the arts, she blends creativity with storytelling across media. Her works include Think.Build.Create and children’s books like Kitchen Khichdi, Remember Me, and Yoga with Mr. Foxx. She also hosts Magic Ink, an audiobook podcast that brings stories to life. An avid traveler and explorer of India’s art culture, Divya weaves her experiences into her writing, art, and music. You may connect with her on Instagram @sierrashine2023

or check out her Blog on Medium: divyaramachandran.medium.com

Please visit:

Our Sponsor